We all have different relationships with money. This stems from our upbringing: what we learned from our parents, school, or society. Understanding how behavior affects financial decisions allows us to use our money better.

This article will touch on two main biases: cognitive biases and emotional biases.

Being biased means you tend to lean in one direction for or against something.

When you have a cognitive bias, you have a “systematic error” in thinking. This is your brain attempting to simplify things for you and fill in any blind spots in your thinking. Cognitive biases lead you to make irrational decisions.

There are several cognitive biases we exhibit when it comes to financial decisions: conservatism, confirmation, mental accounting, framing, and availability.

Emotional biases are caused by feelings that deviate us from rational decisions. We’ll touch on five emotional biases: loss aversion, overconfidence, self-control, endowment, and regret-aversion.

Cognitive Biases

Conservatism Bias

When people exhibit conservatism bias, they don’t sufficiently update their existing beliefs when presented with new information.

For example, let’s say that Jack recently learned about the rising performance of cryptocurrencies since their debut in 2009. He buys some and the value of his crypto portfolio keeps rising. The following year, new information comes to light that might negatively affect the prices of cryptocurrencies. Instead of updating his beliefs about the performance of crypto and selling them for a profit, he holds on to his prior belief that they are “still performing well” — and makes a loss. If he had incorporated the new information into his trading decisions, he could have avoided losses.

To avoid this bias, consider all pieces of information — both old and new — before making a decision.

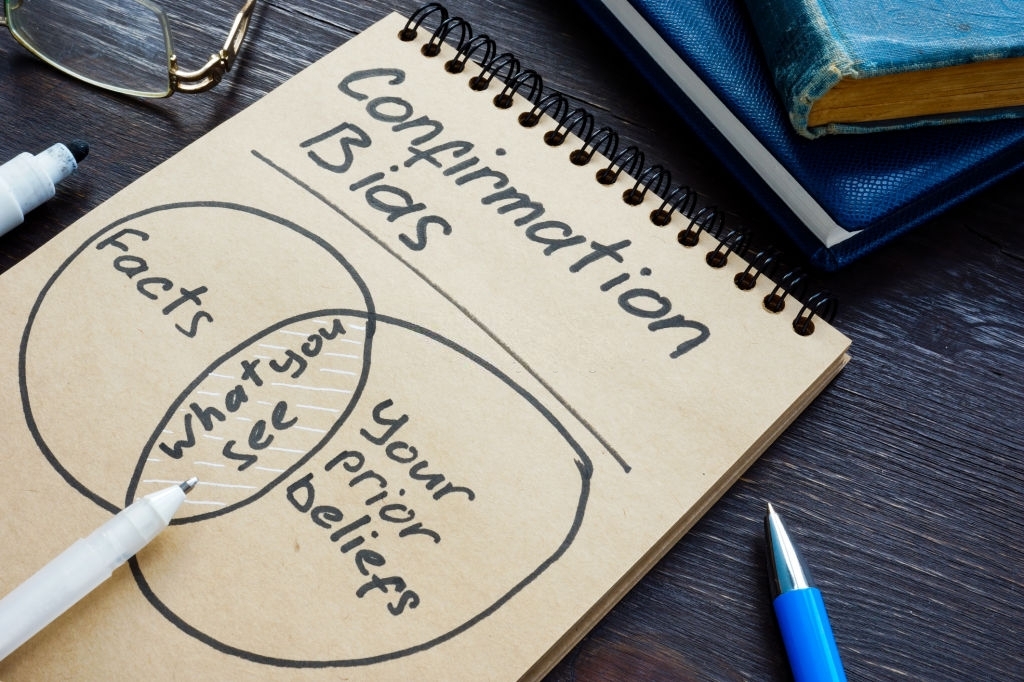

Confirmation Bias

We tend to look for information that confirms our beliefs and reject information that contradicts our beliefs.

For example, say you learned that pharmaceutical companies did well during the pandemic. You then find a pharmaceutical company whose stock you can afford. Because you are dead-set on adding a pharma company to your portfolio, you look for information that justifies you investing in that company. You also overlook or reject any negative information: e.g., if someone told you that the company had critical issues with their corporate governance, you’d point out that they were producing a new, game-changing vaccine — anything to make you buy the stock.

Being critical and rational — and seeking out opposing information — is key to making good financial decisions.

Mental Accounting Bias

If you’ve ever placed a different value on your salary versus the money you received as a gift, then you’ve exhibited mental accounting bias.

This bias makes us divide money into mental buckets and stops us from viewing our finances holistically. We have buckets for “college”, “retirement”, “holiday”, “car”, “wedding”, “money markets” etc. We don’t use the “wedding” money for retirement because we know the wedding is a year away and the money in that bucket is more important now than retirement. That’s mental accounting bias at work.

For example, say Mary got her salary at the end of the month and birthday money from her dad. She decides to use her salary to buy groceries and make loan repayments but blows the birthday money on entertainment. She effectively placed her salary in the “important things” bucket and her birthday money in the “entertainment” bucket. But money is fungible; the money from the gift could have been used to buy groceries and part of her salary could have gone towards entertainment.

When it comes to money, we should place the same value on every dollar so we can view money holistically.

Framing Bias

Consider these two sentences:

- “There is a 70% chance that you will achieve your financial goal if you buy into Investment X”.

- “There is a 30% chance that you will lose all your money if you buy into Investment Y”.

From those two questions, which investment sounds more appealing? Investments X and Y are the same, just framed differently: X is framed from a “gain” perspective and Y from a “loss” perspective. Depending on how the question is framed, people will gravitate toward Investment X and be skeptical about Investment Y.

Framing bias is an erroneous cognitive process where we make decisions based on how options are framed, whether negative or positive.

This bias may cause you to lose money (by ignoring the negatives) or miss out on good investments (by underrating the positives). To avoid this bias, try to remain neutral at all times. Look at both the benefits and drawbacks of any investment or transaction so you can make an informed decision.

Availability Bias

Availability bias means basing decisions on information that you retained or saw recently without doing extensive research. Let’s look at a few examples.

Millie recently started a policy with an investment provider, Investo. When she signed up, things were good, until the market took a turn and she lost money. When she wanted to take her money out, Investo informed her that the policy is new and that taking the money out would trigger high charges. She now blames Investo for losing her money and decides to write a bad review about the product.

Abed, a new dad, wants to start saving for his child’s education. He does his research and comes across Investo, reads the negative online reviews, and decides not to invest with them.

A few days later, Abed’s colleague brings up wanting to invest and mentions Investo. Abed quickly dissuades his colleague from investing with them because they will lose money — but Abed only said this because it was the last thing he read about the company that he could recall easily.

To avoid availability bias, do more research beyond just what you easily recall.

Emotional Biases

Emotional biases are based on how you feel. They include loss aversion bias, overconfidence bias, self-control bias, endowment bias, and regret-aversion bias.

Loss aversion bias

We hate losses more than we love gains. Losing $500 hurts more than earning $500 makes us happy. Because of this, we tend to hold on to losing investments and sometimes take on more risk to avoid losses.

For example, let’s say Mr. Nagasaki is preparing for his retirement and fears that his pension won’t be enough to cover his retirement needs. He invests a huge lump sum into the stock of another company. Three months later, the stock price falls sharply due to a scandal, and the value of Mr. Nagasaki’s portfolio drops. However, instead of selling his stock, he holds on to it and decides to invest even more money hoping the stock price will rise. This is loss aversion bias at work.

Loss aversion bias can also make you sell your profitable investments too quickly in fear of a future loss. If Mr. Nagasaki had made a profit on his stock, he would sell at a lower profit margin to avoid any future losses — to his detriment.

All investments have risks. Know that losses can occur, be rational, and do extensive research to avoid loss aversion bias.

Overconfidence Bias

Overconfident people attribute success to their doing and failure to external factors.

For example, Mary, who studied medicine, may overestimate her ability to pick pharmaceutical stocks. If the stocks do well, she attributes it to her superior knowledge. Should the stocks fall, she blames it on other factors like bad luck or the FDA.

Being confident is good, but confidence should stem from objective research. More importantly, if something doesn’t go according to plan, take accountability and go back to the drawing board to see where you can improve.

Self-Control Bias

Self-control bias happens when we prioritize instant gratification over delayed gratification.

For example, Thomas buys local income-paying bonds because he can spend the coupons today. The risk here is that bonds don’t have much room for capital growth compared to equities. His future is at risk because when the bond matures and he gets back the bond’s face value, he’d have consumed all his income and have little to no growth. If he had at least re-invested those coupons in the stock market, he would have enjoyed capital growth and would have diversified between an income and a growth asset.

You can overcome self-control bias through discipline: being intentional and decisive about your future financial freedom and foregoing short-term gains.

Endowment bias

Antonio’s grandfather recently passed away, and in his will, he left his car wash company to Antonio. When Antonio sits with the company’s accountant, he learns that the company isn’t doing too well and that the most rational thing is to sell the company. But because he’s sentimental, Antonio refuses to sell the company and keeps running it in honor of his late grandfather.

Antonio is exhibiting endowment bias: the tendency to value owned assets higher than what they’re actually worth. If Antonio didn’t have any rights to the company, he would have sold it. But because he has rights and a sentimental attachment to it, he places a lot more value on it than warranted.

Endowment bias usually manifests itself when it comes to inherited assets. It is hard to avoid this bias, but asking questions such as “Will letting go of this asset benefit me holistically?” helps bring a rational, unbiased perspective to the discussion.

You can also ask the previous asset owner (before they pass away), “Are you leaving this asset/business for us to manage in perpetuity, or can we sell it?”. The answer will indicate whether you should sell the asset or not.

Regret aversion bias

Regret aversion bias causes you not to take certain actions that you might regret later.

For example, when suffering from regret-aversion bias, you may hold on to an investment longer than necessary because you think the stock price might rise after you sell. You may also find yourself ignoring a good investment out of fear that you might regret it later.

You might also follow the herd by investing in something merely because everyone else is doing so. If everyone then loses, the regret or emotional burden is minimized.

The antidote to regret aversion bias is more research. The more you understand the potential benefits and risks of an investment, the better you can reduce your risk and enhance returns.

Avoid biases

Understanding your biases is a great step toward making better financial decisions, and cognitive biases are easier to correct than emotional ones. This is because cognitive biases center around your logical processes and thinking, but emotions are more deeply rooted — so adapting to an emotion is usually the best option. Speaking to a certified financial advisor can also help you work through your biases.